A walk to the Pakistani Spaza shop in my neighbourhood took me back to the Apartheid era in the mid-70s. During that time, you would never see young people loitering on street corners smoking dagga. In the townships, the city council police patrolled the streets demanding pasboeks from Black men aged 18 and above. Across the CBDs of all the country’s cities, the South African Police also patrolled for the same reasons. There was nowhere for a Black man to hide. There was no shortage of jobs then. And strict laws barred the sale and use of drugs like dagga. Smokers of this ‘herb’ faced imprisonment if caught with dagga in their possession.

Fast forward to the advent of democracy, and townships across South Africa have been flooded with all kinds of illegal drugs. Rising unemployment is a major factor contributing to the socio-economic distress. Greasy youngsters are a common sight on street corners or outside the Pakistan Spaza shops, snorting all sorts of illegal substances available to them. It is no secret that the Pakistani Spaza shop owners have clandestine partnerships with township drug lords and stock these illegal drugs in their shops. The presence of illegal drugs in the townships has become normalised. Residents feel under siege as crime, such as house robberies, becomes rampant. Young people steal anything—water taps, garden tools left outside, and parents’ groceries—to feed their addiction. The police are paralysed and hopelessly incapable of managing the situation, further hampered by their own ignorance and corruption. Residents allege that some police officers are on the payroll of drug lords and inform dealers about police raids. They also claim that when they tip off the police about drug dealers, the police notify the dealers that they have been snitched on. Consequently, residents are reluctant to report criminal activities.

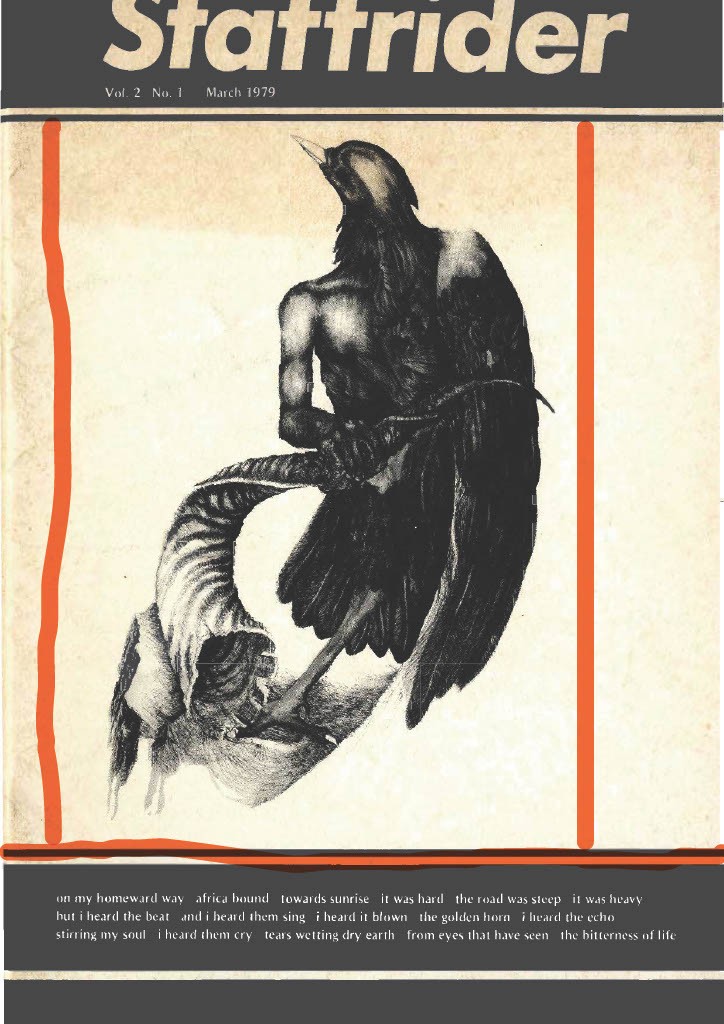

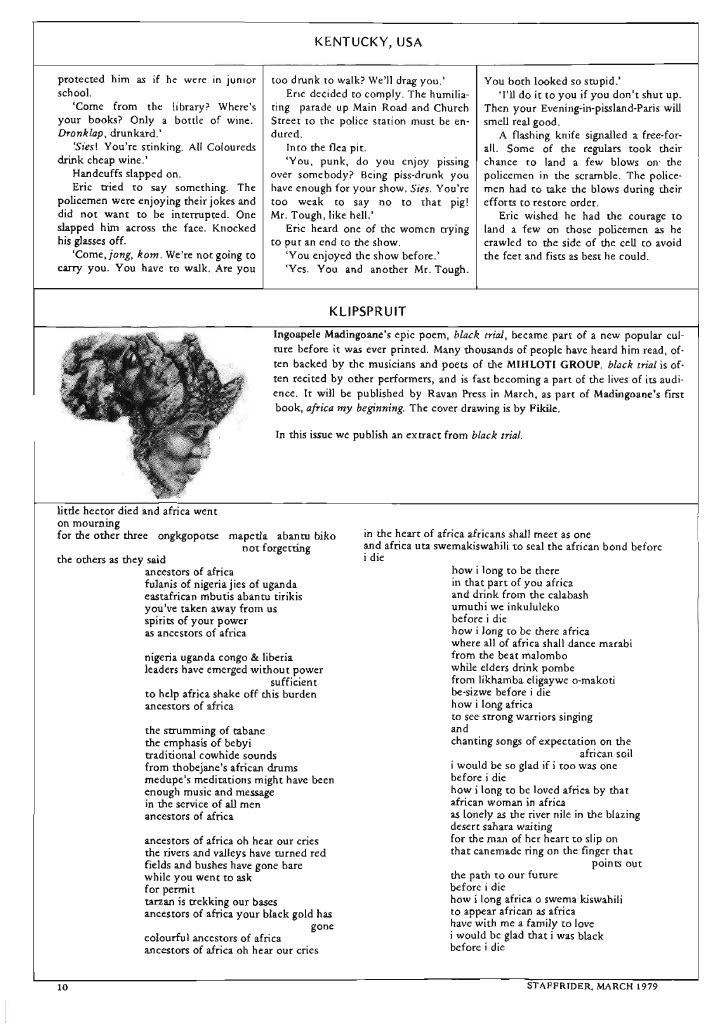

During Apartheid, young Black people endured harsh conditions that did not grant them the freedoms now enjoyed by youth under democratic rule. During that era, young individuals participated in various cultural groups and activities, which fostered the emergence of notable writers, poets, painters, and musicians across the townships of this country. Legends such as Mtutuzeli Matshoba, Kanakana Lakhaimane, Nape a Motana, Nthabeni Phalandwa, Matsemela Manaka, Egune Skeef, Ingoapele Madigoane, Fikile Zulu, David Phoshoko, and many others stand as testaments to the resilience of those who lived under apartheid. These people fought against the oppressive system through their voices, artwork, and literature, and some witnessed the fall of apartheid. The iconic literary magazine, Staffrider, provided a platform for many young Black South Africans to express their sentiments against apartheid. It was no surprise, then, when the Nationalist regime banned Vol 2 No 1 March 1979 of Staffrider

. Source: Staffrider, Vol. 2 No. 1, March 1979, published by Ravan Press.

Leave a Reply